Mechanical Turk

The Mechanical Turk was a fake chess-playing machine constructed and unveiled in 1769 by Wolfgang von Kempelen to impress the Empress Maria Theresa of Austria.

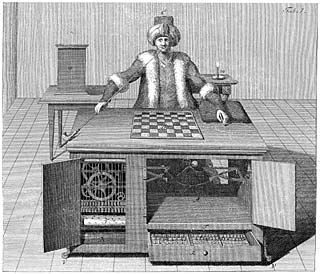

Copper engraving by Wolfgang von Kempelen or by Johann Friedrich von Racknitz

The automaton consisted of a life-sized model of a human head and torso, dressed in Turkish robes and a turban, mounted behind a large cabinet housing a clockwork machinery. On top of the cabinet stood a chessboard.

Following the death of Wolfgang von Kempelen in 1804, his son sold the Mechanical Turk to Johann Nepomuk Mälzel, (he patented the metronome, invented by Dietrich Nikolaus Winkel) who took it on tour around the world.

The chess-player was a mechanical illusion that allowed a human chess-master hiding inside to operate the machine. The director avoided detection by moving forward or backward on a sliding seat when the cabinet doors were opened in proper sequence. For nearly 85 years the Mechanical Turk won most of the games played during its demonstrations around Europe and the United States.

Among the challengers were :

- Count Ludwig von Cobenzl (1769 / 1770)

- Reverend Louis Dutens (1770)

- Sir Robert Murray Keith (1774)

- Grand Duke Paul of Russia (1781)

- Charles Godefroy de la Tour d’Auvergne, Duke of Bouillon (1783)

- Benjamin Franklin (1783)

- Frederick the Great, Prussian King (1785)

- François-André Danican Philidor (1793)

- Napoleon Bonaparte (1809)

- Eugène de Beauharnais, Prince of Venice and Viceroy of Italy (1811)

- Charles Babbage (1819 / 1821)

- Charles Caroll (1827)

- Edgar Allan Poe (1835)

Johann Nepomuk Mänzel died at sea in 1838 and the Mechanical Turk changed hands several times. Finally the automaton was donated to Nathan Dunn’s Chinese Museum in Philadelphia where it was destroyed during a fire in 1854.

Clockwork Game

Personalized copy of the Clockwork Game Novel

Jane Irwin, a self-published comic creator, writer and artist from Kalamazoo, Michigan, retold the story of the Mechanical Turk in her newest graphic novel Clockwork Game. The project was succesfully funded on October / November 2013 on Kickstarter. I was one of the (humble) backers and supporters of the project. I received today my personalized copy of the trade paperback of the Clockwork Game. It’s a beautiful artwork.

The novel is a historical fiction, but it sticks very close to the historical facts. The story starts in May 1769 in Schönbrunn, Vienna, when Herr von Kempelen presents his chess-automaton to her Majesty, Empress Maria Theresa. The story ends in July 1854 when the Mechanical Turk is destroyed in the fire touching Dunn’s Chinese Museum in Philadelphia. Échec was the last word of the machine.

MTurk

The name Mechanical Turk is also used by Amazon for it’s crowdsourcing Internet platform that enables requesters to co-ordinate the work of humans to help the machines of today to perform tasks for which they are not suited. This Amazon Web Service (AWS) labelled MTurk was launched in November 2005.

Small tasks are posted as HIT’s (Human Intelligence Task) by the requesters (individuals or businesses) at the marketplace for work. Turk Workers (also called Turkers) can browse the available HIT’s and execute them (if they are qualified) for a monetary payment set by the requesters. The average wage for completing tasks is about one dollar per hour.

MTurk is also used as a tool for artistic or educational exploration. One example is Aaron Koblin‘s collaborative artwork The Sheep Market displayed, among others, at the Hall of Fame of Digital Art at Leslie’s Artgallery.

Bibliography

The following list provides some links to additional informations about the Mechanical Turk:

1. ancient original documents

- 1783 – K. G. v. Windisch : Briefe über den Schachspieler des Herrn von Kempelen (Google Books, 33 Seiten))

- 1783 – Journal des Sçavans : Lettres de M. Charles Gottlieb de Windisch sur le Joueur d’échecs de M. de Kempelen; traduction libre de l’allemand (BnF Gallica bibliothèque numérique, 2 pages)

- 1784 – Carl Friedrich Hindenburg : Ueber den Schachspieler des herrn von Kempelen: nebst einer Abbildung und Beschreibung seiner Sprachmaschine (Google Books, 45 Seiten)

- 1784 – Berlinische Monatszeitschrift, Dezember 1784 : Schreiben über die Kempelischen Schach-spiel und Redemaschinen + Zusatz zu diesem Schreiben (Google Books, 20 Seiten)

- 1784 – Johann Philipp Ostertag : Etwas über den Kempelinschen Schachspieler

- 1789 – Joseph Friedrich zu Racknitz : Über den Schachspieler des Herrn von Kempelen und dessen Nachbildung (Universitätsbibliothek Humbold-Universität zu Berlin, 71 Seiten)

- 1819 – Erneuerte vaterländische Blätter für den österreichischen Kaiserstaat : Die wiedererstandene von Kempelen’sche Schachmaschine (ÖNB/ANNO, 4 Seiten + Schluss)

- 1821 – Robert Willis : An Attempt to Analyse the Automaton Chess Player of mr. de Kempelen. To which is Added a copious Collection of the Knight’s Moves Over the Chess Board (Google Books, 40 pages)

- 1836 – Edgar Allan Poe : Maelzel’s Chess Player (MOA digital library, Southern Literary Messenger, Vol 2, issue 5, 8 pages)

- 1839 – George Walkers : Anatomy of the Chess Automaton; Fraser’s Magazine for Town and Country, Volume 19 (Google Books, 15 pages)

- 1841 – Beilage zu Nr. 155 des Adlers für 1841 : Das Geheimnis des berühmten Schach-automaten (ÖNB/ANNO, 3 Seiten + Schluss)

2. reprints of ancient documents

- 1784 : Philip Thicknesse : The Speaking Figure and the Automaton Chess Player, Exposed and Detected; ISBN 978-1170687338

3. contemporary books and documents

- Tom Standage – The Turk: The Life and Times of the Famous Eighteenth-Century Chess-Playing Machine; ISBN 0425190390

- Tom Standage – Mechanical Turk: The True Story of the Chess Playing Machine That Fooled the World; ISBN 978-0140299199

- Gerald M. Levitt – The Turk, Chess Automaton; ISBN 978-0786429035

- Tom Robertson and Matt Fullerty – Napoleon versus The Turk, When the Master Warrior Met the Master Machine; ISBN 978-1937056964

- Bill Wall : The Chess Automatons

- Chess News : Von Kempelen’s Chess Turk recreated ; Heinz Nixdorf Museum in Paderborn

- John Edwards : The Turk on stamps

- chessgames.com : database with 7 games of The Turk (automaton)

- BBC News Magazine : A Point of View: Chess and 18th Century artificial intelligence

4. Videos

- Chess master automaton The Turk Hoax resurrected by rich guy

- Napoleon Bonaparte Chess Game vs The Turk – The most famous person ever to lose to a machine!

- The Turk – chess playing automaton robot model

- Secret of Kempelen